1.0 Introduction

This article is based on my years of teaching urban planning research as a subject, engaging in urban planning research as a consultant, and acting as a research advisor to professionals and post-graduate students. Urban and regional planning is a discipline that addresses issues and challenges in the built and natural environment. Urban planning is a deliberate process of managing and shaping the physical development of cities, including land use, transportation networks, infrastructure, and public spaces [1]. The broad goal of this process is to create a functional, sustainable, and socially equitable settlement, which is carried out through the preparation of development plans and initiatives.

However, we cannot develop a plan for an area before we understand it[2]. Before planning, we must understand the planning area, its peculiarities and other issues. Understanding these needs is where applied research in urban and regional planning comes in. Applied research is conducted to offer practical solutions to real-world problems. An example is a post-occupancy evaluation of residential housing units to inform local authorities on how residents are experiencing a newly developed housing project[3].

To extract information for development planning to address issues such as land use management, housing provision and affordability, environmental management, public health, general infrastructure provision and mobility issues, among others, urban and regional planners rely on applied research; this helps to capture the prevailing situation in the study area, helps to ensure planning decisions consider the local communities’ peculiar situation, identify prevailing development pattern and addresses complex societal challenges.

Applied research enhances urban planning outcomes, as with every other endeavour, in areas such as economy, finance, economic management, public health, and technology. Applied research helps to resolve real-world problems. Notably, the applied research structure could be different for urban planning academics than for urban planning consultancy engagement. Applied research is tied to various modes of urban planning. In this article the explanation of applied research is tied to academic and consultancy urban and regional planning activities, and significant aspects of applied research are covered in this article (Figure 1). The article’s main objective is to help urban planning researchers, practitioners, and students (undergraduate and post-graduate students) have a robust understanding of applied research processes in urban and regional planning.

2.0 Identifying Research Problems

Urban planning research begins with identifying specific challenges or issues faced in a prospective plan area, either urban or rural. Some of these challenges or issues could be urban sprawl emergence, inefficient transportation systems, poor housing environment, deficit housing supply, lopsided local economic development, ageing population, public health issues, increasing crime rate, lack of gender inclusiveness in settlement development and environmental degradation, among others. Problem identification involves assessing these issues within broader local contexts. The issues mentioned earlier must be examined carefully beyond the symptoms. For instance, housing shortages in a specific area could be due to one or multiple factors: population growth, regulatory barriers, inadequate finance, rigid development control processes, and housing market inefficiencies, among others. A robust problem-identification process ensures that research questions are both relevant and actionable. This implies that formulating urban planning research questions is premised on a robust planning problem and issues identification. It should also be stated that problem identification could be refined based on the outcome of data collection for specific urban planning issues in any given settlement. The process of defining a problem requires basic data support[4].

For example, as an urban planner within a given city, you observed that a certain segment has a higher petty crime rate than others, negatively impacting the security, livability and the local community’s economic growth. You will then proceed to identify a series of issues attached to this crime rate; this process is further improved through reading through published local development reports, police reports, and judicial reports, among others, to further establish crime pattern and rates. Planning research problems could be derived from the day-to-day urban planner practice in the academic, public, or private sector, from reviewing previous project reports, reading local news publications, or from input from residents of the local community. To resolve identified planning problems highlighted in the previous discussion, specific questions need to be generated, which will be answered during the research. Also, research aim need to be developed in addition to specific research objectives.

3.0 Research Questions, Aim, and Objectives

After identifying the research problems for a given planning area or planning topic, turning the problems into question format ensures that urban planners have a more concentrated approach to providing solutions to planning problems and issues. Research questions provide a focus and a direction to research. Research questions translate planning challenges and planning topics into specific areas of enquiry. The structure research questions take is determined by the nature of the planning study, topic or project.

Broadly, research questions can be categorised into descriptive, analytical, evaluative, and policy-oriented. Descriptive research questions seek to highlight urban issues and patterns. Example: What are the main factors contributing to mobility issues (traffic congestion) in the city centre? Answering this question requires traffic volume, land use, and transport infrastructure data. Analytical research questions explore relationships between planning research variables. Example: How does the availability of affordable housing influence population density in urban settlements? This question requires assessing housing affordability indices, demographic trends, and land use patterns. Evaluative research questions determine the effectiveness of implemented urban planning policies, development plans or interventions. Example: To what extent has the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system reduced travel times in the study area? This question requires comparing travel data before and after BRT implementation in the study location. Policy-oriented research questions focus on planning solutions. Example: What housing affordability policies can address the high cost of public and private housing units in an urban area? The answers to such questions would inform policy recommendations.

Academic research aim and objectives or planning project aim and objectives need to be developed. The research aim clearly states the planning study’s purpose or project. In applied urban planning research, aim should align with practical concerns to solve a real-world challenge or issue. Aim defines the intended outcome and ensures that research findings contribute directly to the body of knowledge or ensure practical planning solutions and strategies. For instance, if a study focuses on housing shortages, the aim could be to examine the factors contributing to inadequate housing supply towards proposing planning interventions on housing supply. Notably, a well-defined aim establishes the direction of the research and ensures relevance to urban planning practice. For planning consultancy projects, research aim are shaped by the client’s needs or the project area’s planning challenges. For example, a local council focused on addressing mobility issues could conduct a research to understand and resolve the mobility issue. The research aim will be to identify mobility problems and propose planning strategies to address the local council mobility challenge adequately.

Research objectives are to break down research aim into specific, measurable, and actionable components. A research objective is expected to help understand the effectiveness of existing planning interventions, for example, the level of effectiveness of any previous mobility initiatives in the local council, causes of identified planning issues, dictate the data collection, analysis, and interpretation process and recommendations on the identified planning issues and research topic. Another example is a study on an informal settlement development process and its impact on residents’ living conditions. This study’s research objectives will include an assessment of the land tenure processes, socio-economic conditions in the settlement, regulatory issues contributing to sprawl development, and the impact of settlement conditions on dweller wellbeing. Therefore, research objectives aid in measuring these identified factors to achieve the research aim.

4.0 Literature Review

A literature review ensures urban planning research builds on existing knowledge. A literature review in urban planning academic research helps define research questions, establish theoretical frameworks, and highlight the study’s relevance. In contrast, the literature review of the urban planning practice project report identifies best-case studies and acts as a guiding principle for planning projects. It should be noted that the planning academic research report is expected to have a literature review section, but the urban planning consultancy project report might not have a standard literature review section as obtained in the academic research report.

Broadly, a literature review provides urban planners with a foundation for their work, synthesising findings from other research work, official publications, and relevant urban planning projects. More importantly, a literature review helps urban planners identify gaps in the existing body of knowledge concerning a particular research topic or planning project, showing areas that need further exploration.

Academic urban planning research requires a structured literature review to establish the study’s foundation in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews in academic research serve three primary functions: to clarify research questions, establish a theoretical foundation of the study and highlight the study’s significance by justifying the study’s contribution to the existing body of knowledge[5]. For urban planning project reports, a literature review enables the identification of similar projects and the selection of the best case study to serve as a reference point for the proposed project, establish guiding principles for the proposed project, and also guide in the formulation of policy for the proposed planning project. For urban planning academic reports, the literature review is foundational, while for urban planning consultancy projects, the literature review provides supporting evidence for recommendations.

5.0 Research Design

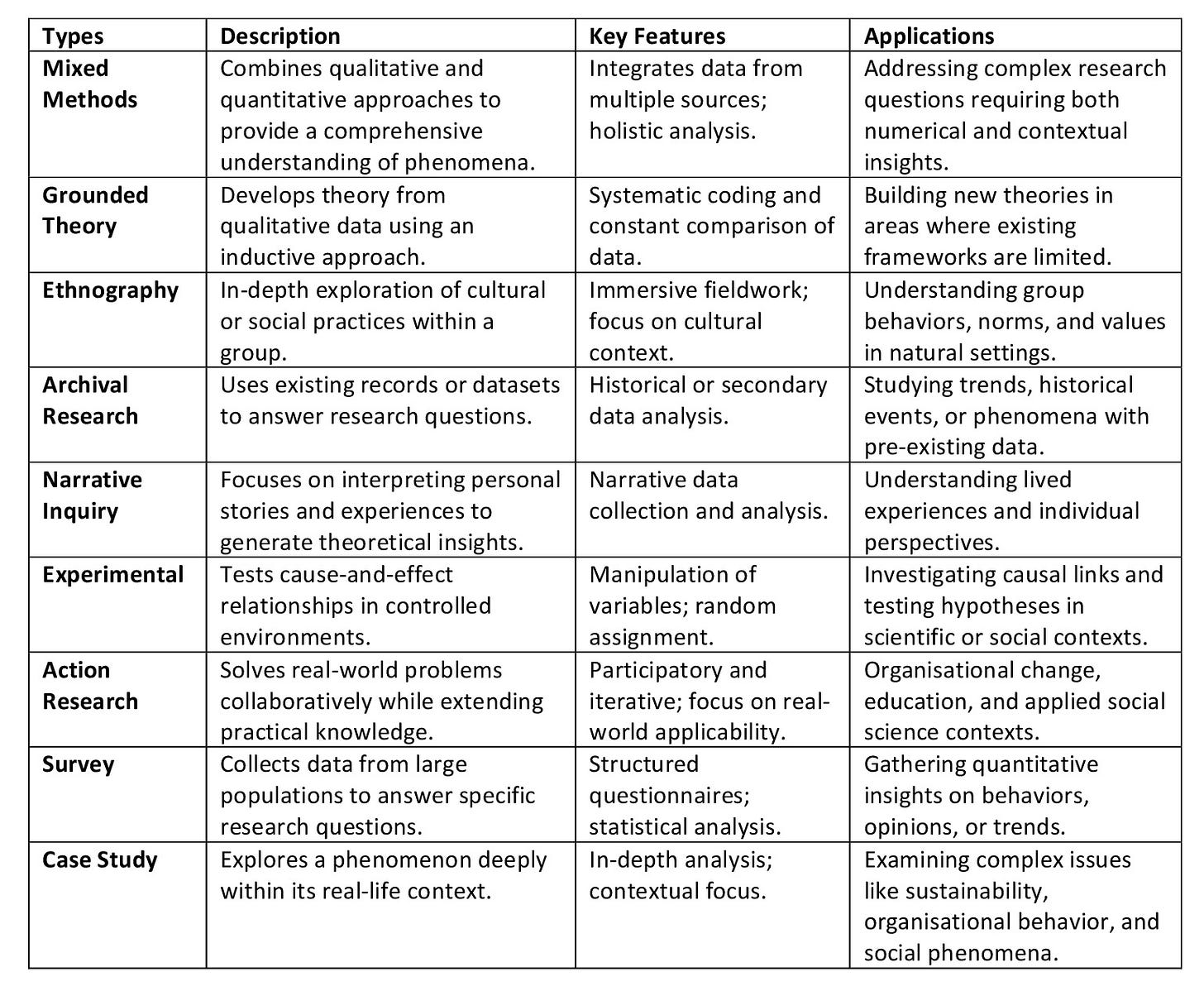

Research design is the process of deliberately planning for a research task. It serves as a framework that directs how the research topic is addressed, data is gathered, and analysis is carried out. Research design is an essential part of the research process and guides the study’s goals with the procedures needed to accomplish them. The nine main research design strategies are mixed methods, grounded theory, ethnography, archival research, narrative inquiry, action research, survey, and case study[6]. As shown in Table 1, each technique has distinct qualities and is appropriate for particular research questions and objectives.

6.0 Research Methodology

Research methodology gives detailed steps to the process or phases of the study from start to finish, emphasising the types of research instruments and methods required to collect and analyse representative data[7]. Research methodology focuses on both quantitative and qualitative dimensions of research. Quantitative methods use numerical data and statistical analysis to identify trends, correlations, and predictive models in urban planning issues, ensuring objectivity and enabling large-scale generalisation. Qualitative methods explore non-numerical data to understand urban planning issues using interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic observations; this allows urban planners to capture different perspectives on any given planning challenge or issue.

7.0 Data Collection in Urban Planning

Data collection is a critical phase in the urban planning research process; this research stage serves different purposes, including answering the research questions, refining the research problem, and ascertaining the magnitude of a research problem. Urban planning data are often location-specific, including population, economy, housing, transportation, environmental conditions, public health, and physical development intensity. Data is the collection of variables and observations explaining the features of the study subjects. Data can be quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative data are data in numerical format, while qualitative data are data in texts, narratives, visual materials, etc., to describe the feature of a variable.

Primary data collection methods include surveys, interviews, and field observations, while secondary collection data often involves census reports, GIS data, and policy documents. Primary data are newly collected data, while secondary data are data that have been previously used for either academic research or consultancy projects. Urban planners rely on primary and secondary data for academic writing and consultancy work engagement. Data dimensions include variables and attributes; variables are the logical groupings of attributes, while attributes are characteristics of people or things, and observations are all the study subjects presented in a dataset. In the dataset, attributes are the columns in a spreadsheet describing the attributes of the observations (Figure 2).

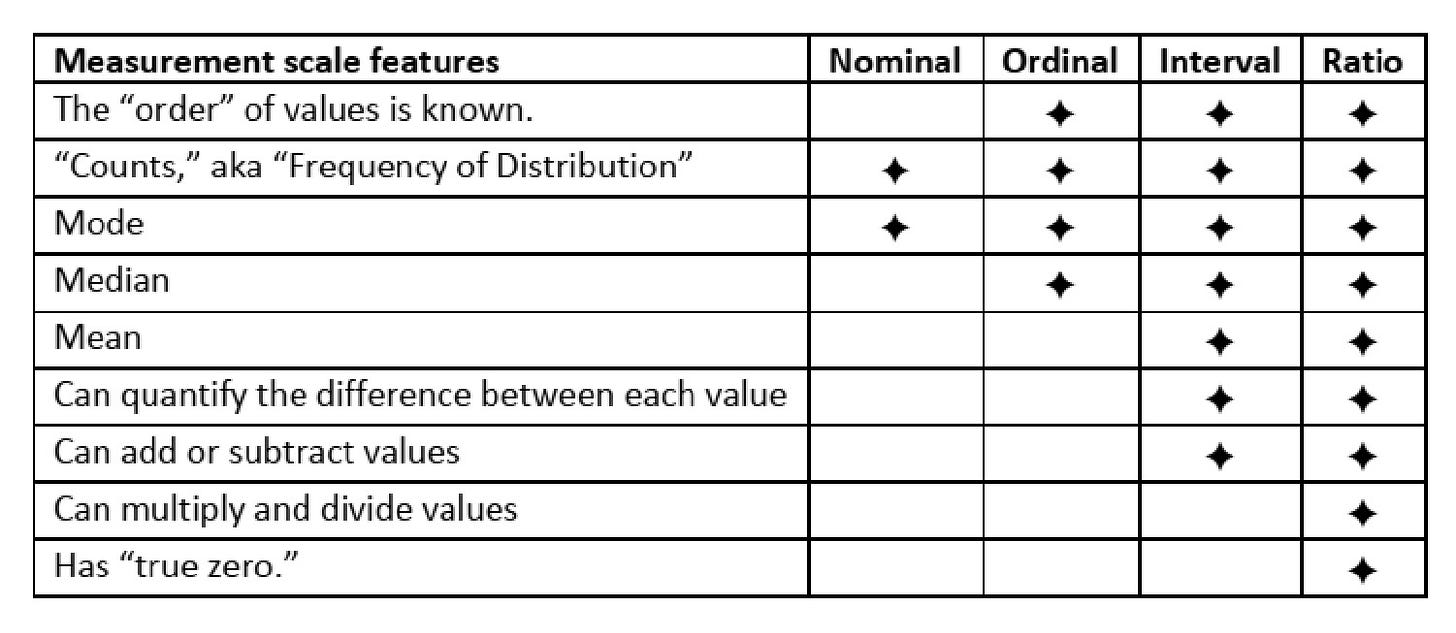

Data levels of measurement (measurement scale) are nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio. Nominal variables are used to “name” or label a series of values. Ordinal scales provide good information about the order of choices. Interval scales give us the order of values + the ability to quantify the difference between each one, and ratio scales give us the ultimate–order interval values plus the ability to calculate ratios since a “true zero” can be defined (Figure 3).

Effective data collection, in addition to other parameters, is also premised on the sampling process; this helps to determine the representativeness of sample coverage. In data collection, there is a need to differentiate between census data and sample data; census data explores the attributes and characteristics of all the elements in a study population, while sample data only explores a subset of all the elements in the study population. Study populations can be human beings, animals, places, or organisations. Census is usually time-consuming, expensive, and often statistically unnecessary; therefore, sampling is necessary.

Sampling methods depend on research objectives. The sampling method could either be probabilistic or non-probabilistic. Probabilistic sampling ensures representativeness, while non-probabilistic techniques do not focus on representativeness but are suitable for targeted studies. For any given urban planning project or academic research report, if representativeness is important and sample data will be used to generalise for the whole population, it is recommended that probability sampling techniques be adopted.

8.0 Data Analysis in Urban Planning

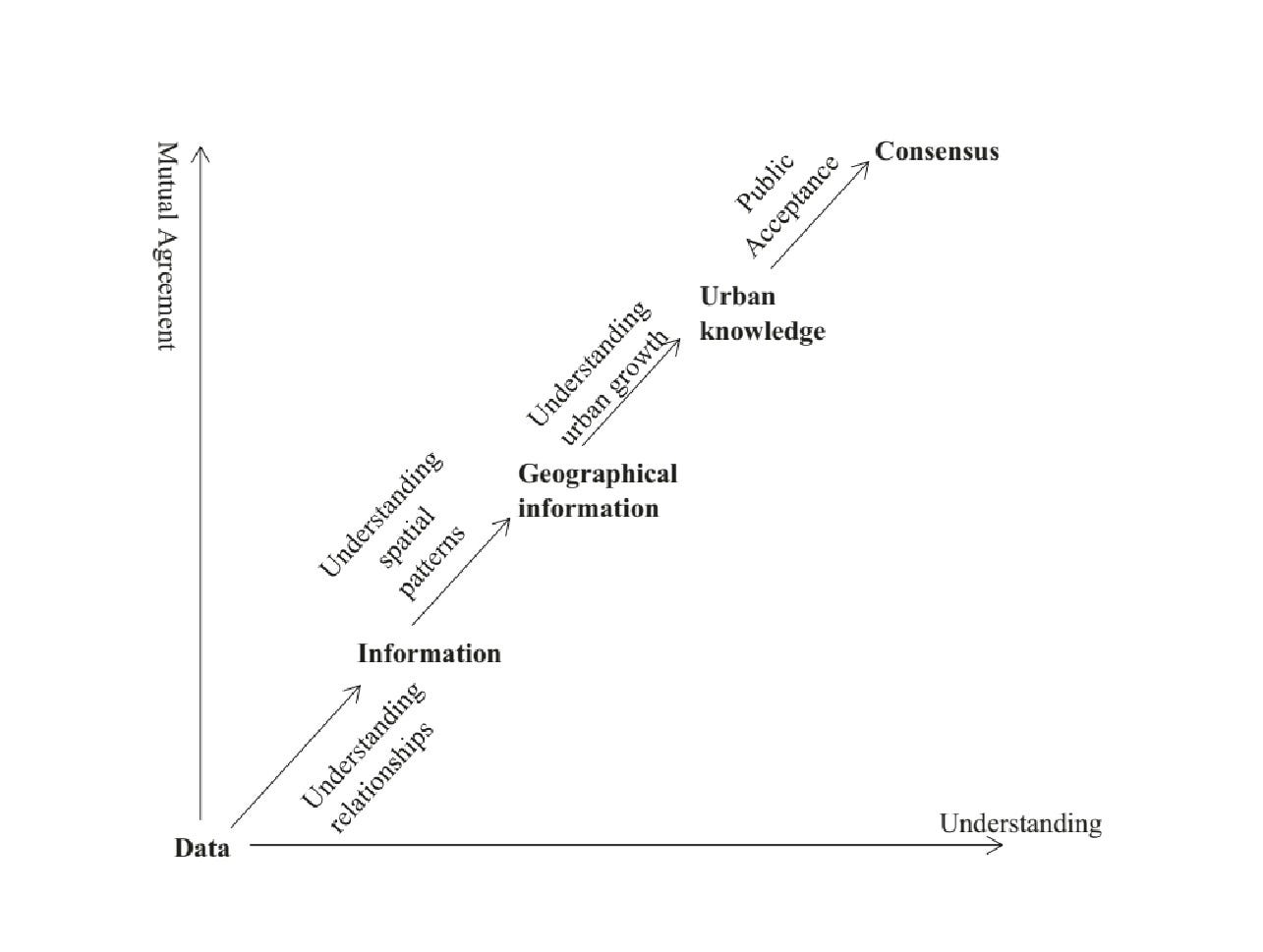

For urban planners to provide suitable solutions to identified problems, there is a need to understand the local community dynamics; this is possible through collecting relevant data and analysis of collected data using both descriptive and inferential statistical tools to draw inferences for planning proposal development. Data analysis translates raw data into planning information for planning actions (preparation of development plans such as local plans, master plans, regional plans, and structure plans, among others). Urban planning information results from urban planners’ interpretation of collected data based on the outcome of different levels of statistical analysis of quantitative and qualitative data from a specific plan area (Figure 4).

Once the data is collected, describing the data is often the first analysis step, regardless of whether it is qualitative or quantitative data. Different methods will be used to explore more complex relationships among variables. For example, for quantitative data regression or correlation analytical tools could be used to probe the statistical relationship between the independent and dependent variables, while for qualitative data methods such as thematic coding, concept mapping, and other forms of qualitative analysis tools could be used to identify pattern in sample responses, this is in addition to basic descriptive analysis of the sample responses.

An independent variable is a variable that we expect to affect a dependent variable; in essence, the dependent variable is subject to the dynamic of an independent variable. For instance, if an urban planner is interested in the crime rate in a local community, data on gender, education, age, unemployment rate, housing condition, and law enforcement effectiveness will be required and used to explain the level of crime in the local community. These variables are independent, while the crime rate is the dependent variable.

9.0 Findings Reporting and Communication

Planners must present the results of planning data analysis to the public, clients, or key interest groups; this could be in the form of a direct presentation of the data analysis outcome or a presentation of a planning proposal (masterplan, urban renewal plan, structure plan, local plan and subdivision plan among others) derived from the result of the planning data analysis. It is expected that the goal of every urban planner is to generate consensus on proposed planning action. This consensus is better achieved through good planning information presentation that educates the planning stakeholders and interest groups. Therefore, urban planning data analysis moves from understanding relationships of observations in the planning area to understanding spatial patterns and urban growth to achieving public acceptance (Consensus) Figure 5.

Effective communication of urban planning findings through well-prepared and reader-focused reports guarantees that the stakeholders will accept the research results. When communicating urban planning findings, either academic research reports or urban planning project reports, visual aids like charts, maps, and infographics are crucial. For instance, a heatmap that displays traffic congestion patterns might be used to illustrate the need for additional transportation routes. Numerous stakeholders with various interests are usually involved in urban planning projects. To address these various needs, urban planners should have customised outputs; for example, for the presentation at policy briefings with policymakers who have limited time to go through a huge volume of reports, planners could use an executive summary report; for the local community planners could use pictorial representation, and for general stakeholder meeting another mode of presentation could be adopted. These suggestions imply that urban planning report communication tailored to each stakeholder’s needs guarantees that relevant stakeholders will easily accept urban planners’ recommendations and suggestions.

10. Ethical Consideration in Urban Planning Research

Research on urban and regional planning is heavily reliant on ethics. When doing research that influences communities, there is a need for accountability, transparency, and integrity. When using surveys or interviews to collect data, informed permission of respondents is crucial. Also, urban planners need to ensure participants know how their data will be utilised; this increases research legitimacy and ensures that participants’ rights are protected.

Urban and rural settlements have diverse sets of people with distinctive cultural and social characteristics; this diversity needs to be respected in urban planning research. For example, urban planning research activities should consider different individuals’, ethnic groups’, religious groups’, and political groups’ viewpoints on any given planning issue.

11.0 Conclusion

Applied research in urban and regional planning ensures that planning decisions are informed by information derived from robust statistical analysis to address real-world challenges such as housing shortages, mobility issues, and environmental sustainability. The research process begins with identifying relevant planning problems and formulating clear research questions, aims, and objectives. A well-structured literature review establishes the theoretical and empirical foundation of the urban planning research or urban planning project, while an appropriate research design ensures coherence in the study.

Research methodology, data collection, and analysis provide the tools to assess urban or rural settlement conditions, measure intervention effectiveness, and generate actionable insights to achieve the intended research or planning aim. Ethical considerations remain central to the research process, ensuring transparency, inclusiveness, and respect for diverse urban and rural settlement populations. Findings must be communicated effectively to stakeholders, policymakers, and communities to facilitate informed decision-making and consensus-building.

[1] Peter Hall, Mark Tewdwr-Jones, 2019. Urban and Regional Planning, 6th Edition, Routledge.

[2] Isserman, Andrew M. 2000. Economic base studies for urban and regional planning. In: Lloyd Bodwin and Bishwapriya Sanyal (eds.). The Profession of City Planning. New Brunswick, NJ: Center for Urban Policy Research, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

[3] Jacques du Toit. Research Design. In The Routledge Handbook of Planning Research Methods, Elisabete A. Silva, Patsy Healey, Neil Harris, and Pieter Van den Broeck (Eds). Routledge, 2015.

[4] Yanmei Li and Sumei, Zhang Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning, 20222. Springer.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill. Research methods for business students (9th ed.). Pearson Education, 2023.

[7] Opoku, A., Ahmed, V., & Akotia, J. Choosing an appropriate research methodology and method. In V. Ahmed, A. Opoku, & Z. Aziz (Eds.), Research methodology in the built environment: A selection of case studies. Routledge. 2016.

[8] Xinhao Wang & Rainervom Hofe. Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning. Springer, 2007.

[9] Li and Zhang, Applied Research Methods. pg. 72