Lecture note prepared by Tpl. Adeleke Akinpelu, MNIM, AITD, MNES, MGARP, RTP, the principal consultant at SMC Professional Services, Lagos, Nigeria. The note is for the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners Professional Examination, 700 level. In most cases, I omitted references and citations. Enjoy your reading and for clarification please reach out through smcinsights@gmail.com or smcprofessionalservices@gmail.com

LANDUSE AND TRANSPORTATION PLANNING

Land Use

Land use implies the use a particular is put to. Land use is the various ways in which land and its resources are been utilized by different people, such as farming, mining, building, and grazing. Land use is how, and the purpose for which, human beings employ the land and its resources. Land use involves both how the biophysical attributes of the land are manipulated and the intent underlying that manipulation – the purpose for which the land is used. Land use denotes the human employment of land. There are different classifications of the use of land, these classifications include residential, commercial, industrial, institutional, public, open space, infrastructural, and mixed land uses.

Land Use Planning

Land use planning is a term that is often used interchangeably with town planning, urban planning, regional planning and urban design. Land use planning is used in the allocation of space for different purposes in a local, regional, or national setting. Land use planning is used to encompass the process of managing change in the built and natural environments at different spatial scales to secure sustainable outcomes for communities. It includes both spatial elements, such as the physical design and layout of neighbourhoods, cities and regions, as well as strategic considerations that take account of social, economic, cultural and environmental factors. The development of local and regional statutory plans is an important component of implementing land use planning as an expression of agreed public policy.

Transportation planning:

Transportation is the movement of people, goods and services from one region to another to meet human socio-economic means. Transportation planning is a preparation planning to move/transfer a human, animal or other items from some place to another place. Also, it involves the management and operation of systems and networks designed to facilitate the movement of people and goods from one place to another. It covers multi-modal, motorised and non-motorised movement by road, rail, water and air. Transportation planning is the development of a comprehensive plan for the construction and operation of transportation facilities. It is a cooperative process involving users of the system – the business community, community groups, environmental organisations, commuters, freight operators, and the general public through a proactive public participatory process. This planning will be related to the operation of the highway system, geometry, and the operation of traffic facilities. Functions of transportation planning include: identifying transportation system components; identifying transportation models, dynamics and interplay; achieving efficient management of transportation resources and reducing a negative impact on the traffic system.

Transportation Planning Period

Short Term (Action Plan): Review matters that can be completed within three years and involve high costs. Example: a programme to optimize the use of existing transportation systems by installing various traffic control devices such as signs and signals.

Long Term ( ≥ 5 years): This type of planning is more structured and complicated and it must be designed better than short-term planning, Urban transportation planning process involves planning the next 20 to 25 year

Notable Transport Problems

There are diverse transportation issues notable are the urban transportation problems of traffic congestion and parking difficulties; longer commuting; public transport inadequacy; difficulties for non-motorised transport; less public space; environmental impacts and energy consumption; accident and safety; freight distribution issues; poor and inadequate planning; weak intermodal coordination and also worthy of note is the neglect of rural transport system.

Transportation Planning Process

Situation/Problem definition: Involve all of the activities required to understand the situation that gave rise to the perceived need for transportation improvement.

Goal and objective: To describe the problem in terms of objectives to be accomplished by the project. Objectives are statements of purpose such as reducing traffic congestion, improving safety etc.

Studied/Research stage: research and analysis that shows the current demand and the relationship of movement with the environmental demands. Information about the surrounding area, its people and their travel habits may be obtained.

Forecast stage: formulating the plan, predicting future travel demand and making a recommendation to fulfil traffic demand. A detailed assessment and forecasting in terms of distribution of area, population, employment, economic, social and land use activities.

Plan evaluation stage to assess whether the proposals made satisfactory demand and provide maximum benefit to the community. To estimate how each of the proposed alternatives would perform under present and future conditions

Implementation: Once the transportation project/plan has been selected, the project moves into the detailed design phase which each of the components of the facilities is specified

Monitoring and Review

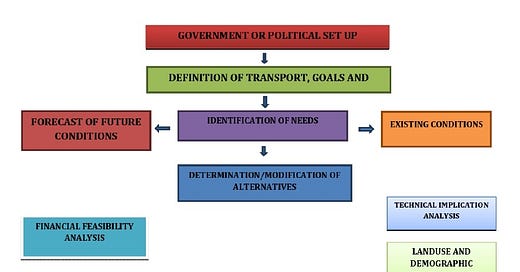

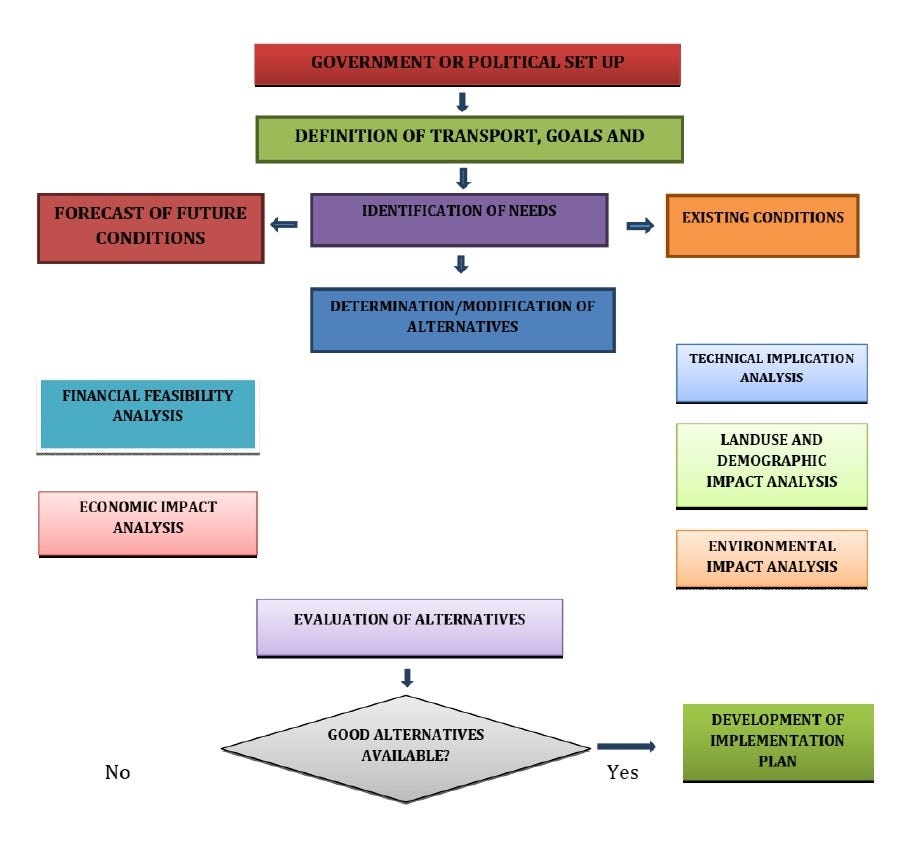

Figure 1: Transportation Planning Process

Transportation, Transportation Planning and Landuse Connection

There is a connection between transportation and land use; a relationship exists between the transportation system as a service function and all the other land-use activities in the city. There is no doubt that transportation is a form of land usage, with this there is a vibrant relationship between the two phenomena. Transportation systems and land use patterns influence each other. Roads, transit, and other transportation elements shape land development, throughout history, predominant forms of transportation have had distinct impacts on the form, density and character of the city (city land use and structure). Also, the distribution and types of land use affect travel patterns and transportation facilities. A dispersed pattern of low-density development relies almost exclusively on cars as the primary mode of transportation. Alternatively, denser urban centres can combine different land uses in closer proximity, encouraging: walking, biking, transit and other forms of travel.

The need to examine and also integrate transportation and land use in the development process is necessitated by the growing environmental and social impacts of road networks and motor vehicle use. These impacts are widely seen as being exacerbated by a lack of integration between land use and transport planning. Land use planning and transportation infrastructure need to work together. Communities should plan for the future and be aware of how their land use plans will affect the levels of traffic, appearance, and points of congestion on highways.

Land use is understood to affect transport in some significant ways. Dispersed land use patterns are typically linked with high levels of automobile dependence. Conversely, concentrated land use is more commonly linked with lower levels of car use and higher levels of public transport patronage.

Higher residential densities and mixed development can lead to shorter car trips and lower levels of car use.

Traditional neighbourhoods can have shorter trips and lower levels of car use than car-oriented suburbs.

Higher employment density can lead to greater public transport use.

Developments close to public transport can generate higher levels of public transport use.

Traffic volumes and choices of mode of travel are influenced by the location, density, and mixture of land uses.

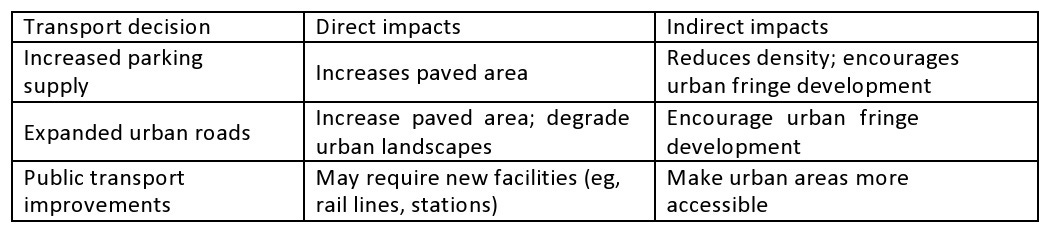

The effects of transport on land use can also be significant. Litman (2007) identifies both direct and indirect land-use impacts that can result from transport (see table below). Direct impacts result from the amount and location of land used for transport facilities (eg, expanded roads, car parks, railways). Indirect impacts arise from transport decisions which affect land use accessibility. For example, an expanded motorway system that improves access to the urban fringe may encourage automobile dependant development and suburban sprawl. On the other hand, transport decisions that result in improvements to public transport can make urban areas more accessible and reduce car dependency. The relationship between land use and transport decisions can be complex and is influenced by a range of socio-economic factors (eg, car ownership, housing demand, and income).

Furthermore, transportation investments have a significant influence on surrounding land uses. Land use patterns also affect the utilization of transportation facilities. These interrelated effects will occur regardless of whether city officials consider land use in determining their transportation investments. Governments, developers, and citizens can work together to design integrated land use and transportation plans that will help achieve a shared vision for the future. Integrating land use and transportation more effectively can help shape priorities for transportation investments and ensure that new transportation projects and land use plans support and reinforce each other. The above statements can be further improved by the design of newer development patterns displaying a different street layout and land use. This alternative includes an integration of different land uses in closer proximity by promoting higher densities with a mix of land uses. The principles of this form of development include:

The revitalization of cities and older suburbs with new growth in already-developed areas

The protection of farms, open spaces, and sensitive environments from new development

The reduced cost of building and maintaining public infrastructure and services. Compact communities can be less costly to local governments, allowing communities to spend money on other services.

Table 1: Examples of Transport’s Direct and Indirect Impacts On Land Use

Since all human activities cannot be concentrated on one point, there is a need for travel to meet divergent needs for shelter, recreation, work, social interaction, and religious and commercial activities. These activities have varying spatial requirements and levels of compatibility therefore land uses are sorted and located based on ease of access to the urbanites, accessibility and space requirement of the land use and compatibility thus giving rise to the need to overcome what is called the “Friction of distance” through transportation. On the other hand, some land uses and associated activities depend on transport routes for their survival thus the city centre because of its accessibility is characterized by a high density of commercial and other tertiary and quaternary activities.

The city centres usually account for a small percentage of the total urban space yet it has the highest density of vehicular and pedestrian traffic, the highest day-time population and the highest concentration of offices and shops. For instance, it was observed that the centre of Warsaw occupied only about 4.5% of the area of the city yet it had 35.7% of its jobs including 90% of those in finance and insurance, 59% of those in shops, stores and commerce. Journeys to this central area accounted for 51.5% of all passengers carried by public transport and 75% of all vehicular traffic. Land use factors such as density, mix, connectivity and walkability affect how people travel in a community. This information can be used to help achieve transport planning objectives. The set of relationships between transport and land use can be briefly summarized as follows:

The distribution of land uses, such as residential, industrial or commercial, over the urban area determines the locations of human activities such as living, working, shopping, education or leisure.

The distribution of human activities in space requires spatial interaction or trips in the transport system to overcome the distance between the locations of activities.

The distribution of infrastructure in the transport system creates opportunities for spatial interactions and can be measured as accessibility.

The distribution of accessibility in space co-determines location decisions and so results in changes in the land-use system.

Changes in the intensity of land use as its use result in changes in the traffic associated with it, the nature and intensity of many different activities carried on in the buildings of a city determined how the movement of people and goods is organized. At the same time the facilities for movement, the capacity of roads and public transport undertaking are themselves the determining factors in the location of these activities. Wegener and Furst (1999) have examined the impact of transport policies on land use and the impact of transport policies on transport patterns. An empirical investigation in the city of Ibadan by Fadare (2010) concluded that for efficient transportation system depends on the diligent and careful collection and analysis of a wide range of such relevant data. He noted for the city of Ibadan, for instance, that the travel demand for a private mode of transportation is most likely to increase in the future with growing car ownership, rising population and increasing proportion of households in the medium and low-density areas and that growth in travel demand may be expected to be faster than population and area growth.

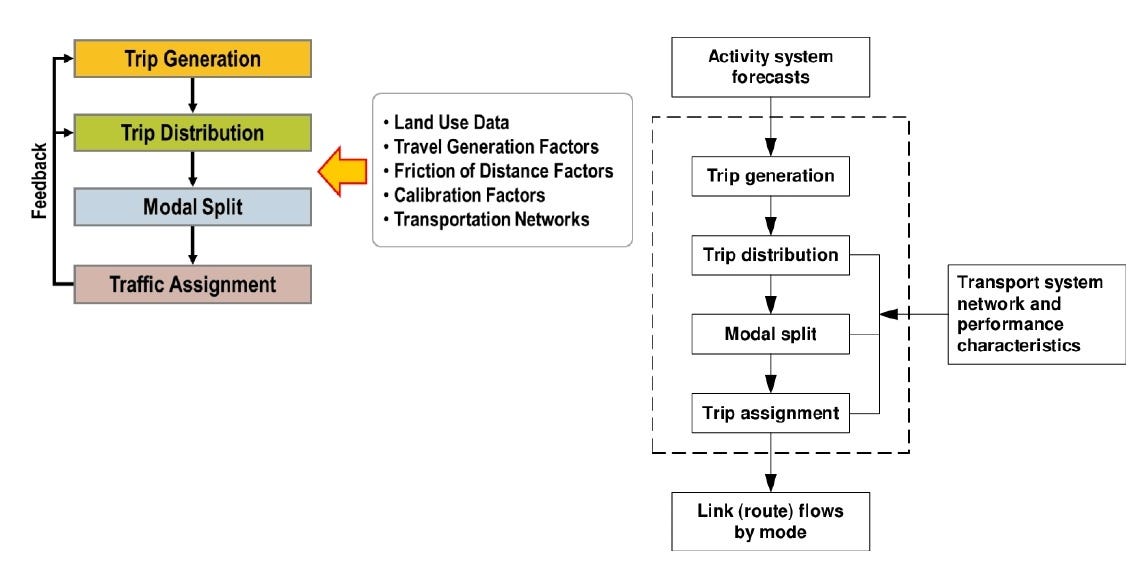

TRAFFIC GENERATION, DISTRIBUTION, MODAL SPLIT AND ASSIGNMENT

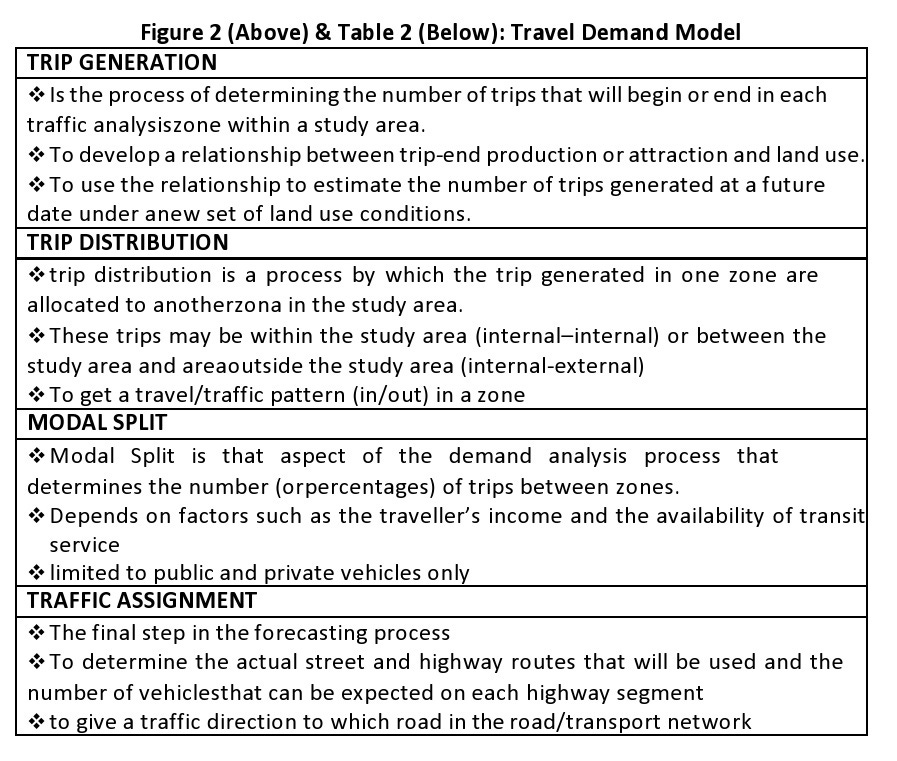

Conventional sequential processes for estimating transportation demand that is often called the “four-step” urban transport process, are:

Step 1—Trip Generation (Should I make a trip)

Step 2—Trip Distribution (Where should I go)

Step 3—Mode Choice (What mode of transport to use)

Step 4—Trip Assignment (Which route to use)

The serial nature of the process (trip generation, trip distribution, modal choice, trip assignment) is not meant to imply that the decisions made by travellers are made sequentially rather than simultaneously, nor that the decisions are made in exactly the order implied by the four-step process. For example, the decision of the destination for the trip may follow or be made simultaneously with the choice of mode. Nor is the four-step process meant to imply that the decisions for each trip are made independently of the decisions for other trips. For example, the choice of a mode for a given trip may depend on the choice of mode in the preceding trip.

In four-step travel models, the unit of travel is the “trip,” defined as a person or vehicle travelling from an origin to a destination with no intermediate stops. Since people travelling for different reasons behave differently, four-step models segment trips by trip purpose. The number and definition of trip purposes in a model depend on the types of information the model needs to provide for planning analyses, the characteristics of the region being modelled, and the availability of data with which to obtain model parameters and the inputs to the model. The minimum number of trip purposes in most models is three: home-based work, home-based non-work, and non-home-based. In this report, these three trip purposes are referred to as the “classic three” purposes.

Step 1: Traffic Generation

The first model of travel demand is used in the transportation planning process to predict which zone of the traffic flow. The purpose is to estimate the number of trips of each type that begin or end in each location, based on the amount of activity in an analysis area. In most models, trips are aggregated to a specific unit of geography (e.g., a traffic analysis zone). The estimated number of daily trips will be in the flow unit that is used by the model, which is usually one of the following: vehicle trips; person trips in motorized modes (auto and transit); or person trips by all modes, including both motorized and non-motorized (walking, bicycling) modes. Trip generation models require some explanatory variables that are related to the trip-making behaviour and some functions that estimate the number of trips based on these explanatory variables. Typical variables include the number of households classified by characteristics such as number of persons, number of workers, vehicle availability, income level, and employment by type. The output of trip generation is trip productions and attractions by traffic analysis zone and by purpose.

Step 2: Traffic Distribution

The second model in the transportation planning process is to get a travel/traffic pattern (in/out) in a zone and shows the total traffic in a certain time, distance and cost. Trip distribution addresses the question of how many trips travel between units of geography (e.g., traffic analysis zones). In effect, it links the trip productions and attractions from the trip generation step. Trip distribution requires explanatory variables that are related to the cost (including time) of travel between zones, as well as the amount of trip-making activity in both the origin zone and the destination zone. The outputs of trip distribution are production-attraction zonal trip tables by purpose. The model of external travel estimates the trips that originate or are destined outside the model’s geographic region (the model area). These models include elements of trip generation and distribution, and so the outputs are trip tables representing external travel.

Step 3: Modal Split

This step estimates the number of trips by different types of transport and focuses on public and private transport only. In this step, the trips in the trip distribution step are split into trips by travel mode. The mode definitions vary depending on the types of transportation options offered in the model’s geographic region and the types of planning analyses required, but they can be generally grouped into automobile, transit, and non-motorized modes. Transit modes may be defined by access mode (walk, auto) and/or by service type (local bus, express bus, heavy rail, light rail, commuter rail, etc.). Non-motorized modes, which are not yet included in some models, especially in smaller urban areas, include walking and bicycling. Auto modes are often defined by occupancy levels (drive alone, shared ride with two occupants, etc.). When auto modes are not modelled separately, automobile occupancy factors are used to convert the auto-person trips to vehicle trips before assignment. The outputs of the mode choice process include person trip tables by mode and purpose and auto vehicle trip tables.

Step 4: Route Assignment

The trip assignment is the final step in the four-step process. This step consists of separate highway and transit assignment processes. The highway assignment process routes vehicle trips from the origin-destination trip tables onto paths along the highway network, resulting in traffic volumes on network links by the time of day and, perhaps, vehicle type. Speed and travel time estimates, which reflect the levels of congestion indicated by link volumes, are also output. The transit assignment process routes trips from the transit trip tables onto individual transit routes and links, resulting in transit line volumes and station/ stop boardings and alightings.

Purpose of the Travel Demand Model

This process is important to be in transportation planning to provide a new transportation system framework, improve the existing transportation system; enhance the development of highways and transit systems; determine the number of trips that will use the existing transportation system.

Travel Demand Model Broad Summary

Individuals or households choose which activities to do during the day and WHETHER TO TRAVEL TO PERFORM THEM (trip generation), and, if so, AT WHICH LOCATIONS TO PERFORM THE ACTIVITIES (trip distribution), when to perform them, WHICH MODES TO USE (modal split), and WHICH ROUTES TO TAKE (trip/route assignment).

METHODS OF TRAFFIC FORECASTING, ORIGIN AND DESTINATION SURVEYS

Forecasting is an educated guess for the future based on objective analysis (to the extent possible) and it should be noted that despite inaccuracy forecasting is better than not forecasting at all. Transportation studies in the planning process focus on Origin and Destination Study (O-D); Traffic Volume Studies; Spot Speed Studies; Travel time and Delay Studies and Parking Studies.

Origin and Destination Study (O-D)

The purpose of O-D is to show the pattern and nature of daily trips made by the residents and to plan for an improved transportation system. The application of O-D includes the determination of traffic flow; determining whether the existing road system is adequate or not and determining the suitable option for a planned transportation system and predicting the traffic pattern in the future.

Traffic Volume Studies

Traffic volume studies focus on the collection of data on the number of vehicles/pedestrians that pass a point during a specified period; to know whether the existing road can accommodate the vehicles that use the road and ensure the smooth movement of vehicles and traffic safety. Application of traffic volume data includes design for road rehabilitation; studying traffic at an intersection; studying traffic control systems; forecasting/predicting traffic volume; studying traffic accidents and analysis of costs-benefits for transport projects.

Spot Speed Studies

This is conducted to estimate the distribution of speeds of vehicles in a stream of traffic at a particular location. Also carried out by recording the speed of a sample of vehicles at a specific location. It should be noted that this is valid only for the traffic and environmental conditions that exist at the time of the study. The application of spot speed data is to establish parameters for traffic operation such as speed zones, speed limits, and passing restrictions; evaluate the effectiveness of traffic control devices such as variable message signs at the work zone; evaluate/determine the adequacy of highway geometric characteristic; evaluate the effect of speed on the highway and determine speed trends.

Travel Time and Delay Studies

A travel time study determines the amount of time required to travel from one point to another on a given route. Information may also be collected on the location, duration, and causes of delays and data also aid the traffic engineer in identifying problems at the transport project location. Application of time and delay studies data help to determine the efficiency of a route concerning its ability to carry traffic; identification of locations with relatively high delay and the causes for delays; determine the traffic times on specific links for use in trip assignment models; performance of economic studies in the evaluation of traffic operation alternative that reduce travel time and to evaluate the change in efficiency and level of service with time.

Parking Studies

The need for parking spaces is usually very great in areas where land is devoted to high-intensity uses such as residential, commercial and industrial activities among others. The adequacy or not of parking spaces for specific land use affects the level of service. The application of parking data is to get valid information for the parking design project and determine the adequacy of parking spaces.

DESIGN OF ROAD ALIGNMENT, SPEEDS, SITE DISTANT LANES AND CARRIAGEWAYS

Classification of Roads

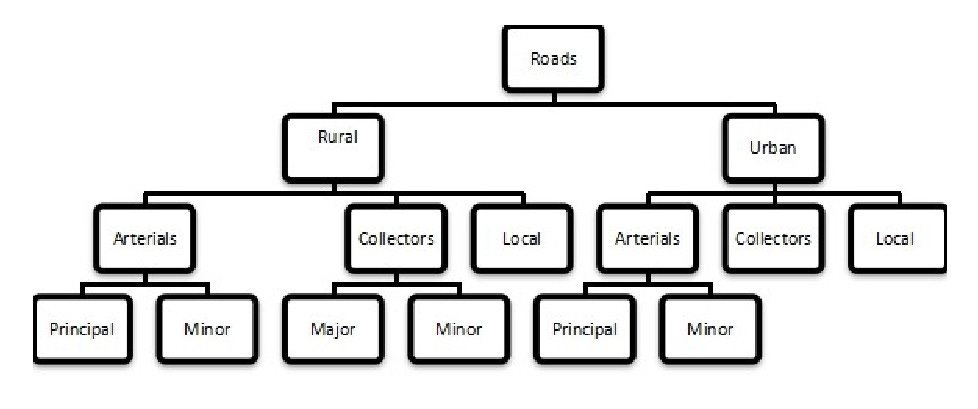

Classification is the process by which streets and highways are grouped into classes, or systems, according to the character of traffic service that they are intended to provide. Roads can be classified in several ways but the two main classifications are “ownership and function”. Ownership refers to who controls the roads, hence we have “Federal Roads”, “State Roads” and “Local Government Roads”. This relates to the control and ownership of the road and who manages the roads. The functional classification is, what role the road performs. There are three highway functional classifications namely: arterial, collector, and local roads. All streets and highways are grouped into one of these classes, depending on the character of the traffic (i.e., local or long distance) and the degree of land access that they allow. These classifications are described in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Roadways Functional Classification

Classification System

Arterials: Provides the highest level of service at the greatest speed for the longest uninterrupted distance, with some degree of access control. Arterials can either be principal or minor both in rural and urban roads. An example of rural and urban arterial roads is shown in plates 1 and 2.

Collectors: Provides a less highly developed level of service at a lower speed for shorter distances by collecting traffic from local roads and connecting them with arterials. Subclasses of collectors are:

Major Collectors: Connect small towns to large towns not served by arterials, link entities with nearby arterials, urban areas

Minor Collectors: Serve remaining small towns, link-local traffic generators with rural areas

Local: Consists of all roads not defined as arterials or collectors; primarily provides access to land with little or no through movement plates 5 and 6 showing an example of local and urban local roads.

Geometric Design of Road

The geometric design of roads is the most important aspect of road construction. The geometric design of a road provides maximum efficiency in traffic operation with maximum safety at a reasonable cost (Gupta and Gupta, 2010). Geometric design is the arrangement of the visible elements of roads such as alignments, grades, sight distances, slopes etc.

Alignments

Alignments consist of both horizontal and vertical alignments. The horizontal alignment of a road must be carefully chosen to have a good correlation with the vertical alignment and the elements such as radius of curvature, design speed, lane width, details of superelevation and adequate sight distance must be adequately considered.

Horizontal Alignments: The primary control elements used to locate a highway in a horizontal plane. Horizontal alignment defines the tangents and curvature of the highway.

Vertical Alignment: The primary control elements used to locate a highway in a vertical plane. It is defined by the profile grade.

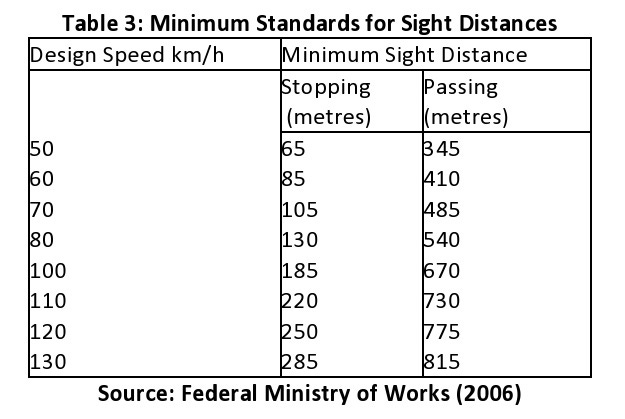

Sight Distance

Sight distance the ability to see ahead, is one of the utmost importance in the safe and efficient operations of vehicles on a road. Sight distances of sufficient length must be provided so that drivers can control the operation o their vehicles to avoid striking n unexpected objects on the travelled way. Two sight distances are considered in the design: passing sight distance (PSD) and stopping sight distance (SSD).

Stopping Sight Distance: Is the minimum sight distance required for a driver of a vehicle travelling at a given speed to bring his vehicle to a stop after an object on the road becomes visible, stopping sight distance is to be provided at all points on multilane and 2-lane roads. It is also provided for all elements of interchanges and intersections at grade, including private road connections.

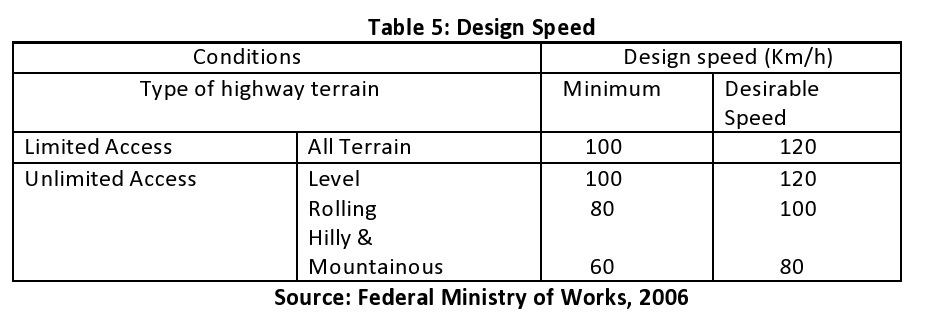

Passing Sight Distance: This is the minimum sight distance that must be available to enable the driver of one vehicle to pass another vehicle, safety and comfortably, without interfering with the speed of an oncoming vehicle travelling at the design speed. Passing sight distance is considered only on a two-lane road. Table 5 shows the minimum standards for sight distances related to design speed.

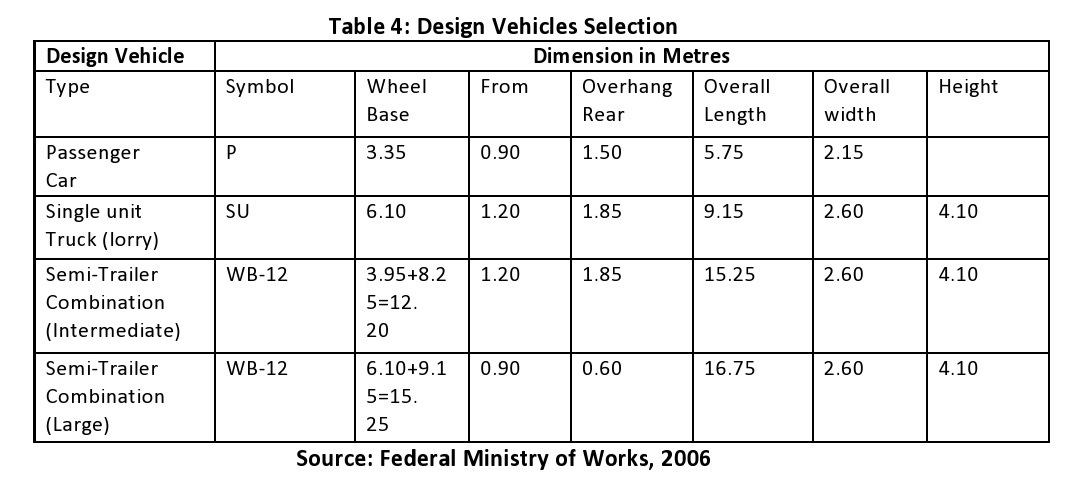

Design Vehicles Selection

The physical characteristics of vehicles and the proportions of various size vehicles using the roads are positive control in geometric design. Design vehicles are selected to represent various classes of vehicles operating on the road (See Table 6). The vehicle type which should be used in the design for normal operations shall represent at least 60% of the total flow. Design of intersections, however including ramps and turnarounds shall allow for the largest vehicle expected to negotiate the designated turns, especially where the pavement is kerbed.

Design Speed

Design speed is a speed selected to ensure efficient vehicle operation having regard to the influence of the physical features of the road an example of design speed used in Nigeria is shown in Table 7. Design speed is the maximum safe speed that can be maintained over a specified section of the road when conditions are so favourable that the design features of the road govern. Vertical and horizontal alignment, sight distance, and superelevation will vary appreciably with design speed. Such features as pavement width, shoulder width, and side clearance are usually not affected. The geometric standard should be established to obtain safe stopping or passing sight distance and to secure the lowest gradient differential or longest vertical curve possible within economic feasibility.

MASS TRANSIT IN URBAN CENTRES

Transportation is the engine that drives the growth and development of people and countries. Mass transit provides the channel through which people, goods and ideas are adequately moved from one location to another. Mass transportation is the movement of a large number of people, goods and services from one place to another in one vehicle. It is therefore inevitable for the socio-economic and socio-cultural integration of nations. Mass transport is characterised by three values and principles namely, equity, accessibility and mobility. The federal government of Nigeria introduced the policy of the mass transit programme in 1988 to lay the foundation for moderately organized mass transit in Nigeria. With the introduction of this policy, the goal of the public mass transit system changed from revenue generation to a government intervention programme aimed at alleviating the socioeconomic problems of the citizenry.

Mass transit, also called mass transportation, or public transportation, is the movement of people within urban areas using high-capacity modes such as buses and trains. The essential feature of mass transportation is that many people are carried in the same vehicle (e.g., buses) or collection of attached vehicles (trains). This makes it possible to move people in the same travel corridor with greater efficiency, which can lead to lower costs to carry each person or—because the costs are shared by many people—the opportunity to spend more money to provide better service or both.

Mass transit systems may be owned and controlled by individuals, private organisations or the public sector (government agencies). The importance of mass transportation is in supporting the mass movement in urban centres. The need for travel is derived because people rarely travel for the sake of travel itself; they travel to meet the primary needs of daily life. Mobility is an essential feature of urban life, for it defines the ability to participate in modern society. Mass transportation systems are varied and have different features. Nevertheless, whether they are land-based (rail or road-based mass transit systems) or water-based, they have a role to play in very large cities, largely because they are often less congesting, have large capacities to move passengers efficiently and are relatively better users of ‘transport space’ (road, tracks etc). Furthermore, mass transit provides a cheap means of transportation compared to private transportation; provides an opportunity to move large numbers of people; reduces the rate of urban traffic congestion and helps ensure the economic success of areas by making it easier and less costly for large numbers of workers and shoppers to enter and leave.

PREPARATION OF A CIRCULATION PLAN/TRANSPORTATION AS AN INTEGRAL PART OF THE COMPREHENSIVE URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN

Concept of Comprehensive Urban Plan

Comprehensive Urban Plan is a comprehensive plan that integrates various aspects of a settlement such as housing, transportation, infrastructure etc. Multidisciplinary: it encompasses various dimension as social, economic, environmental, engineering, architecture etc.; It is a long-term development agenda ad document with a vision for future development. Comprehensive Urban Plan focuses on the rational and most optimal use of land. More importantly, It focuses on efficient uses of resources to meet the present and future requirements of a given settlement. Other areas of consideration for a comprehensive urban plan include environmental sustainability; inclusive planning; affordability; restrictions on ecologically sensitive areas and heritage sites; focus on ensuring a balanced growth of the city and efficient distribution of facilities and, infrastructure.

A comprehensive urban development plan is a plan that intends to address the present challenges of an urban area and also provides for future project needs of the urban area. The comprehensive plan is a long-term planning document that provides a conceptual layout to guide future growth and development of the urban area for example Ikeja, Ilorin, Ado-Ekiki etc. The plan focuses on areas such as housing, health, industry, commercial development and also circulation transportation, so a typical comprehensive development plan as circulation/transportation has a sub-component.

Circulation Plan

The circulation plan guides the continued development of the circulation system to support the planned growth of a settlement. The purpose of the Circulation Plan is to provide a safe, efficient and adequate circulation system for the City. A typical circulation plan focuses on reducing traffic congestion, easing commuting, improving road safety, and maintaining an efficient and effective transportation system. A typical content of a circulation plan will include:

Table of contents

Figures

Tables

Executive Summary

Chapter X: Circulation Plan Background

Chapter X: Circulation Plan Aim and Objectives

Chapter X: Existing Circulation Description

Chapter X: Plan Elements

Chapter X: Project Environment Description

Chapter X: Traffic and Transportation System

Chapter X Transportation, Traffic and Parking Assessment (Road Network, Traffic Flow Characteristics, Traffic Volume Count and Analysis, Origin-Destination Survey, Existing Parking Situation)

Chapter X: Proposed Circulation Plan

Chapter X: Transportation Management Plan Chapter X: Phasing Plan

Chapter X: Conclusion Chapter X: Recommendation

References

Appendices

Note: A circulation plan/transport plan could be included in the comprehensive plan and it could also stand on its own as an individual project and report.

FORMULATION OF TRANSPORTATION POLICIES IN NIGERIA

Policy

A policy can be conceptualized as a set of ideas, guidelines, goals, aspirations, and visions for a better society. Policies are frequently, though not exclusively, incorporated into laws and other legal instruments that serve as a framework for developing planning interventions.

Transport Policy Definition and Overview

Transport policies can be defined as standards, principles, and rules formulated or adopted by the government to accomplish its long-term goals of an efficient transport system. Tolly and Turton, (1995) conceive of transport policy as the process of regulating and controlling the provision of transport to facilitate the efficient operation of the economic, social and political life of any country at the lowest social cost. Transport policy forms the basis for the planning and direction of growth of the transport system and the extent to which the planning and provision of transport provide appropriate solutions. He argues that the approaches to transport provision as well as the efficiency of the transport system are directly related to the nature and dynamism of the transport policy of a country.

Transport policies deal with the development of a set of constructs and propositions that are established to achieve objectives relating to social, economic and environmental development, and the functioning and performance of the transport system. Transport policy can be undertaken by both private and public sectors. Governments, most times are involved in the policy process since they either own or manage many components of the transport system. On the other hand, many transport systems, such as maritime and air transportation, are privately owned and thus have much leverage in the policy process through their asset allocation decisions, which reflects in new public transport policy paradigms.

The public transport policies also serve as a regulatory framework which guides all activities in the sector. The need to develop a national transport policy that is responsible for the needs of the country and its people is essential in developing countries like Nigeria. Transport policy provides the guidelines for planning, development, coordination, management, supervision and regulation of the transport sector with its fundamental goal of developing an adequate, safe, environmentally sound, efficient and affordable integrated transport system within the framework of a progressive and competitive market economy.

The National transport policy by helping to explain the Government’s decisions and actions in the transport sector by espousing the goals and principles that guide it; identifying existing gaps and short-comings and how to address them; showing how actions in the different modes are linked in pursuit of common goals; providing the basis for a system of monitoring and accountability; and Ensuring consistency in the application of policy principles across all modes and in pursuit of different objectives and a good public transport policy will help facilitate financial assistance towards improving urban mobility.

Transport Policy Benefits

The benefits of public transportation policies include the following:

It allows the standards by which the transport sector is governed to be set down, comprehended and followed by everyone involved,

Common strategies are utilized for everyone involved in the public transportation sector and in this way expanding operational proficiency,

Control frameworks are set up in the operational environment inside the public transport sector,

The transportation policies represent the techniques needed to get the maximum benefits in the minimum time,

They are important to train newcomers to the public transport sector and to keep other members completely informed of the agreed policies.

Promote a high-quality urban transport system

Improve productivity and economic growth

Encourage increased accessibility which in turn influences prices and land use

Improve the environment in the city

The Relevance of Transport Policy

Transport policies arise because of the importance of transport in virtually every aspect of the economic, social and political activities of nations. Transport is taken by governments of all types, as a vital factor in economic development. Transport is seen as a key mechanism in promoting, developing and shaping the national economy. Governments also seek to promote transportation infrastructure and services where private capital investment or services may not be forthcoming.

Transport Policy Formulation

While formulating public transport policies, it is important to consider every facet of the transportation unit. The principle areas to be covered in the transportation unit incorporate the following; introduction which gives the reason and the decision behind the formulation of the policies, the transportation administration, the instruments and the language utilized, the rules governing everyday operations, procedures and controls governing the transport sector, established and systematized thought on different theme which have been acknowledged for growth and development in the public transport.

Transportation policy dimension

Social aspects: improve the social aspects as can be done safely and comfortably

Economic aspects: with the existing variety of travel patterns, activities such as employment, population and household income will be increased.

Physical aspects: create an efficient transportation system because there are various modes of transportation introduced

Nigeria’s Transport Policy

The Nigerian Public Transport policy observed the dominance of the road in the transport sector of the country and the increased demand for road transport. The policy likewise acknowledges the large number of small administrators in the sector because of the high costs of vehicles, their poor condition of upkeep and the over-burdening characteristics of the vehicles all of which constitute a different hazard to well-being on and off the roads.

Public transport policies in the past had likewise hampered the formulation, development, regulation, control and implementation of urban transport guidelines. These have to some degree made the idea of the policy difficult and the appraisal of the policy document incomprehensible before implementation. Moreover, the process of formulation of the policy alienates the stakeholders, particularly private sector operators of the transport system as well as the ordinary transport users or riders. The fact that there was little consultation with stakeholders made the previous efforts of putting together a national transport policy on exercises destined for the shelves. Closely associated with the problem of inadequate data and poor consultation, the approaches of government in the evolution of transport policy are the inability of even government-stated policy statements to change over time.

Nigeria’s National Transport Policies

1965 Statement of Policy on Transport

1993 National Transport Policy

2002 Master Plan for Integrated

2003 Draft Transport Policy

2008 National Transport Policy

2010 Draft Transport policy

Transport Policy Implementation in Nigeria

Examples of transport policy implementation include:

The urban mass transit program/ initiative of the federal government,

The shipping policy initiative of the government

Reforms in the transport sector, namely:

Road sector reforms

Port sector reforms

Rail sector reforms

Reforms in the inland waterways sector

The policy on public-private partnership {PPP}

Sustainable Transport Policies

Sustainable transport policies are easily defined, very practical in scope, of the greatest benefit to the poorest sections of society and relatively cheap to implement. Their defining characteristics are a clear commitment to targets and objectives to be achieved over clear time scales. For most Nigerian cities relevant targets and objectives would include:

reducing air pollution and noise levels;

increasing the space, security and comfort for pedestrians and cyclists;

reducing the number of cars and lorries on the roads and increasing the proportion of journeys accomplished by walking and cycling;

developing and improving those modes of transport that are zero pollution on the streets;

establishing safe routes to schools, hospitals, workplaces, etc;

reducing road traffic accidents;

reducing total energy consumption;

increasing the amount of green space in urban areas;

increasing the number of trees.

For Nigeria to have a sustainable transportation system, certain fundamental issues need to be addressed.

The need for continuous investment in the transport sector

More involvement of the private sector - guided privatization

Need to evolve a dynamic transport policy and its effective administration.

Need for appropriately integrated multimodality

Balance in transport and environment development.

Transport and land use planning consciousness.

Increased capacity building in transportation

Efficient and coordinated institutional arrangement

A concerted effort should be made to integrate both rural and urban road networks in Nigeria.

Transport development and consequences should be accorded the right priority for a system to evolve.

Successful solutions have been based on awareness of the necessity to protect the city, not only among decision-makers and citizens but also among businessmen and other interest groups.

Well-planned and coordinated measures step-by-step are necessary for solving the traffic and environmental problems in cities.

The good aesthetic design of street closures, pedestrian streets, stops etc e.g. tree planting are important to improve the city environment

Continuous follow-up studies and environmental impact assessments are necessary to correct and also extend the measures undertaken.

Future steps for making cities more livable and adaptable to sustainable development will be directed to reduce car dependency through more comprehensive land use and traffic planning and offering alternative transport opportunities. Telematics can play a role in giving advanced information on transport alternatives and existing traffic conditions.